Two decades in, interleague play is as progressive (and important) as ever

Baseball has always been a game that has lived as much in its legend as it has in its present. As a result, Major League Baseball respects its roots, if you will, more than the other major North American sports leagues combined. Changes to the status quo are immediately aligned with what has long been in place and subject to intense scrutiny that can sometimes undermine the good that could follow, simply because it is different from what has been.

However, when changes are made to the game, they are often of a sweeping variety. In 1973, the addition of the designated hitter made a game within the larger game and essentially created a different language across league lines. The further division in the game by splinting the two-division league format into three and adding the wild card format in 1994 made for a more widely competitive game, adding a total of four more teams to the playoffs. Then in 2012, an additional wild card slot created the play-in game, which further expanded the competitive reach to encapsulate more teams than ever.

But in regard to changes that have made the game more challenging, inclusive and intriguing, nothing has been able to equal the success of interleague play. For so many years, baseball was unique in the fact that its two leagues had extremely limited interaction. With the exception of spring training, only in the All-Star Game and World Series were teams allowed to cross league lines for competition. In one regard, it added both intrigue and loyalty. American League faithful believed in the more offense-based, attacking style of the game, which was increasingly amplified by the presence of the designated hitter. Meanwhile, the National League became a purists haven, a league that still forced the pitcher to the plate and thus required a more strategic approach to lineup alignment, discipline and usage of the entire roster throughout a game.

There was a time when each league truly operated as a separate entity under one umbrella of Major League Baseball, with the commissioner acting as the intermediary between the two. And although there had long been discussion and intrigue about what an open scheduling slate would look like, no commissioner in the game had ever pulled the trigger on putting those wonders into action until 1997, despite the fact the position of league-oriented presidents had long been stripped of power and eventually merged in 1999.

In the mid-'90s, however, baseball was on life support as it emerged from its ugly labor stoppage and player strike of 1994 and 1995. The game needed to pull out all stops, and this meant putting its old ways to bed and pushing the game forward by any means necessary. The most radical of those efforts was the introduction of interleague play in 1997, which was brought into existence as one part logical evolution, one part capitalizing on an easy way to bait a spurned fan base back into the ballpark.

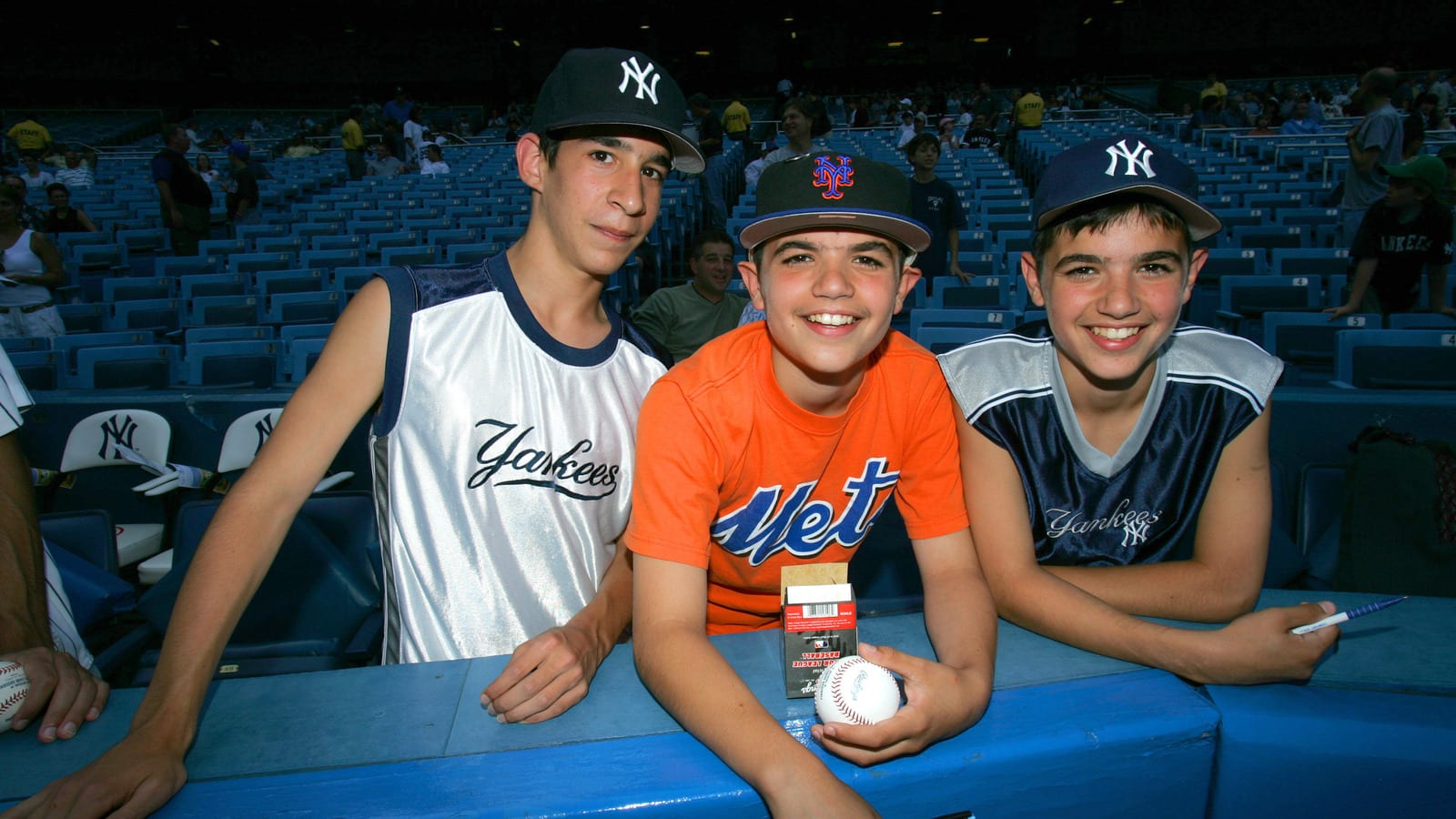

There was a time when a Mets fan and a Yankee fan could inhabit the same neighborhood but never the same ballpark to see their teams face off. Likewise, Anaheim and Los Angeles, despite being separated by less than an hour (give or take a traffic jam), could never face off. Meanwhile in Chicago, the north and south sides of their baseball fandom might as well have been the same as the difference between living in North and South Korea.

In fact, in New York, such was the intrigue of the possibility of a Mets/Yankees pairing that for 19 years the two clubs played an in-season exhibition game to give the fans the chance to see the natural rivals face off. Needless to say, baseball's palette was set for interleague play, and Major League Baseball was not blind to the concept its adherence to tradition was blocking.

It was a decision that was easy to make, and baseball made league warfare its top spectacle on the schedule. Interleague games were blocked into designated chunks on the schedule and often were featured on weekends. While there were a few bland pairings, the allure of seeing the formerly forbidden format take place in real time hit the mark. Baseball still had a ways to go to regain a semblance of its previous popularity, but the trick worked. Interleague play proved that baseball was capable of moving beyond its stuffy, antiquated tendencies in a major way.

The evolution — and forced expansion — of interleague play has opened many previously closed doors in the game. The movement of the Houston Astros to the American League made interleague play a regular part of the daily MLB schedule. This need was eased into play by the restricted exposure of cross-league interaction during the initial phase of interleague scheduling.

Baseball has rebounded completely from those lean days in the mid-'90s and has set financial record after financial record for attendance over the last few years. And while interleague play is not the sole catalyst in achieving this, it has played a vital role in helping expand the game’s interest base.

There are fans of every team in most every city, and the assurance that guaranteed regional rivalry games brings makes for a limited attraction that brings unique fans to the ballpark more often than ever before. The days of having no chance to ever see the Cardinals again if you move to Kansas City (or vice versa) are done; the two teams are guaranteed to play a home and away series each year. In the same vein, it has also helped open new avenues of regional competition, such as what is seen in the DMV area between the Baltimore Orioles and the Washington Nationals, a rivalry that was created by the relocation of the former Montreal Expos to an area where there was a natural rival to mix it up with.

These types of battle lines, along with the natural face-offs between same-city foes, have guaranteed the continual relevance of interleague play, even if its initial novelty has subsided some. Novelty remains in what interleague play is, as the game has still been resistant to completely allowing interleague play to be a free-for-all in the way that it is in the NBA, for example. Divisions still face off against each other in a rotating basis against other divisions, with the exception for "natural rival" games, which are permanent fixtures on the schedule. This important provision allows there to still be anticipation for a long-absent team paying a visit for a home stand. This anticipation has paid off in some forms for a long period of time, such as the return of Albert Pujols to St. Louis, who has faced his former club twice since moving over to the American League’s Angels but still has not made a return to Busch Stadium. Likewise, the long-awaited returns of Ichiro, Roger Clemens and Ken Griffey Jr. were all guaranteed by the rotation that interleague play allows.

The pageantry that has been afforded by the expanded exposure of formerly league-exclusive properties has been great as well. The Yankees draw massive crowds everywhere they go, which allows down-on-their-luck (and attendance) National League teams to see that bump in attendance at least once a year. The ability to participate in the Derek Jeter farewell tour from a few years back, be able to put eyes on the phenomena that are the current Chicago Cubs, or the spectacle that is the talent of Clayton Kershaw, Mike Trout or Bryce Harper is something that should not be limited to 14 other cities only. Baseball needs promotion, and an important vessel toward achieving this is the accessibility that total, live league access brings.

For those who enjoy the nuisances of the game, the advantage/disadvantage of American League teams attempting to adapt to the potential loss of their designated hitters when visiting National League parks continues to add strategic intrigue. Likewise, NL teams attempting to "bulk up" to stand toe to toe with their more powerfully inclined AL opponents on the road remains an fascinating notion as well.

As has been the case with most all barriers that have been feared before the adaptation, interleague play has done nothing but make the game less exclusionary and more interestingly contemporary. What baseball shied away from for so long has now become its normal way of doing things, and despite the ideas that it may, the sky has far from fallen as the MLB has continued to evolve. If anything, it has proved that there are still plenty of ways for an old dog to do some pretty interesting new tricks after all these years.

More must-reads:

- 20 highlights from 20 years of interleague baseball

- Getaway Day: Yankees' dynamic duo putting on quite a show

- The 'Active MLB strikeout leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!